Package By Layer

This design approach is the traditional horizontal layered architecture, where we separate our code based on what it does from a technical perspective.

In this typical layered architecture, we have one layer for the web code, one layer for our “business logic”, and one layer for persistence. Code is sliced horizontally into layers. In an “strict layered architecture”, layers should depend only on the next adjacent lower layer.

In “Presentation Domain Data Layering”, Martin Fowler says that adopting such a layered architecture is a good way to get started. It’s a very quick way to get something up and running without a huge amount of complexity. The problem, as Martin points out, is that once your software grows in scale and complexity, you will quickly find that having three large buckets of code isn’t sufficient, and you will ned to think about modularizing further.

Another problem is that, as Uncle Bob says, a layered architecture doesn’t scream anything about the business domain. Put the code for two layered architectures, from two very different business domains, side by side and they will likely look very similar: web, services, and repositories.

Java Example

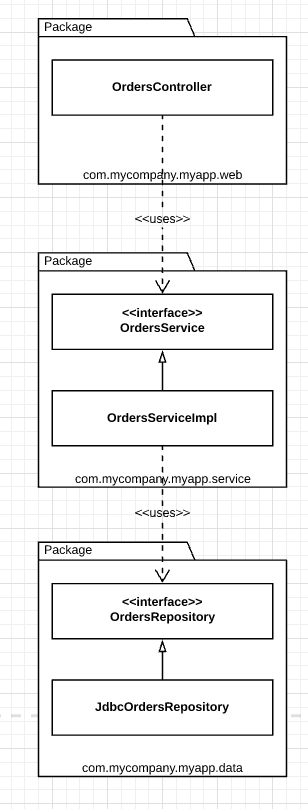

In Java, layers are typically implemented as packages.

In this example, we have the following Java types:

-

OrdersController: A web controller, something like a Spring MVC controrller, that handles requessts from the web. -

OrdersService: An interface that defines the “business logic” related to orders.

Ports and Adapters

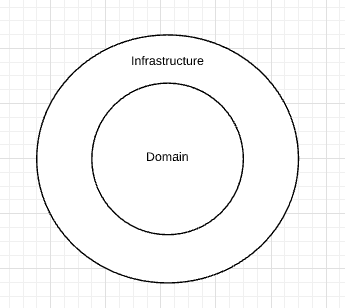

This approach aims to create architectures where business/domain-focused code is independent and separate from the technical implementation details such as frameworks and databases. To summarize, you often see such code bases being composed of an “inside” (domain) and an “outside” (infrastructure).

The “inside” region contains all of the domain concepts, whereas the “outside” region contains the interactions with the outside world. The major rule here is that the “outside” depends on the “inside”.

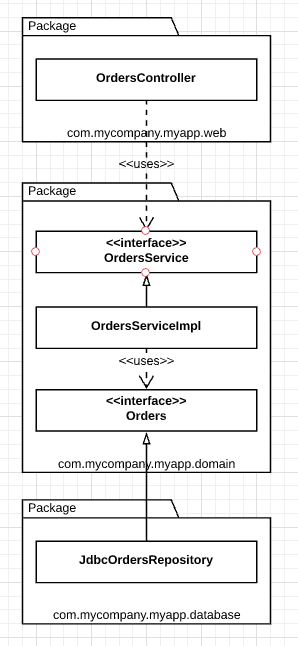

The com.mycompany.myapp.domain package here is the “inside”, and the other packages are the “outside”. Note how dependencies flow toward the “inside”.

OrdersRepository from previous diagram has been renamed to simply be Orders. This comes from the world of domain-driven design, where the advice is that the naming of everything on the “inside” should be stated in terms of the “ubiquitous domain language”. We talk about “orders” when we’re having a discussion about the domain, not the “orders repository”.

It’s worth pointing out that this is a simplified version of what the UML class diagram might look like, because it’s missing things like interactors and objects to marshal the data across the dependency boundaries.

Relaxed Layer Architecture

Layers are allowed to skip around their adjacent neighbor(s).

In some situations, this is the intended outcome (for example, if you are trying to follow the CQRS pattern where you have separate patterns for updating and reading data). In many other cases, bypassing the business logic layer is undesirable, especially if that business logic is responsible for ensuring authorized access to individual recors, for example.

To avoid this scenarios you need a guideline to enforce.

Some teams enforce this through discipline and code reviews.

Some teams use static analysis tools to check and automatically enforce architecture violations at build time. They usually manifest themselves as regular expressions or wildcard string that state “types in package **/web should not access types in **/data” and they are executed after the compilation step.

The problem with both approaches is that they are fallible, and the feedback loop is longer than it should be. If left unchecked, this practice can turn a code base into a “big ball of mud”. It’d be better to use the compiler to enforce the architecture.